Gneiss: A Misshapen Journey

Posted , updatedIntro #

This year I attended DADIU programme as a lead programmer where we built two small games over the course of two weeks and one big game - “Gneiss: A Misshapen Journey” over the course of six weeks. In this post I’ll talk about the production process and technical challenges that we faced when building this game using the Unity game engine.

If you’d like to try out one of our games, you can grab them here:

Production process #

Our team consisted of 23 people: director, art director, producer, 2 QAs, 2 sound designers, 4 game designers, 5 CG artists and 7 programmers. Working in such a large team is an extremely difficult task. Everyone has a lot of ideas and different skill sets. Coming to this programme I expected that there would be a lot of technical challenges, however proper communication was the hardest part.

Pipeline #

Working on this project did not differ that much from regular software development processes based on my personal experiences, apart from the asset pipeline. Rather than just focusing on making sure the code works there was an extra step, we had to make sure that other teams are able to properly quickly get their assets into the game. Due to this the focus from the programmer team essentially was development of tooling and helping out other disciplines with various Unity issues. As a lead programmer, this was pretty much my job the entire time rather than working on features. Personally I enjoyed this a lot as after developing a tool or teaching someone on the team on how to use some specific Unity functionality to integrate their assets provided a tight feedback loop.

Structure #

For our first two games we split up into feature teams where each team would focus on a specific feature, e.g. enemies, main character, etc. Each team would have a certain number of programmers, designers and CG artists, etc. Using this approach the hardest challenge was integrating everything together and keeping an overview of all the features. This approach required a lot of communication for which we were not ready for. In addition to that, we encountered a lot of bottlenecks from the programming side as other disciplines were not comfortable/experienced in using Unity which meant that most asset integration relied on the programmers.

For the final game we dropped feature teams and followed a Scrum model. Each day, we would have a daily meeting in the morning with the whole team where we’d discuss outstanding issues. Then we would split up into smaller discipline groups where we would have our stand-up meetings. We worked like this on a weekly basis, where at the end of the week we would publish a release build. Afterwards, we would do a gameplay demo with the whole team and then discuss the goals for the next sprint. Afterwards we’d split up into disciplines and do a retrospective meeting followed by a sprint planning. This model worked quite well as it was a lot easier to keep an overview of the whole project and greatly reduced communication channels.

Following this model we also managed to resolve the previously mentioned bottleneck on the programmer side. I think this was partially due to the fact that people got more familiar with Unity and Git, but also that we clearly outlined deliverables that discipline must add to the game by individually during the sprint planning sessions.

Platforms #

Initially we used Codecks for managing tasks in our first mini game. It became apparent that in such a large team this platform was not the right fit. It was difficult to split up tasks and keep an overview of what is going on. For the next games we switched to Trello and stuck with that.

For communication, we used Discord. Given how COVID-19 was spiraling out of control during this time, I think this was the perfect platform. We prepared a bunch of text and voice channels per discipline where we discussed specific issues. One thing that worked well here was that the team lads would always sit in the said voice channels and in case anyone has a quick question or didn’t want to bounce messages back and forth, they could jump right in and ask away. To share documents, images, etc - we used Google Drive which worked quite well.

Project setup #

Git #

For managing the source code we used GitLab with a bunch of different Git clients. We chose GitLab as it allowed for most space per project compared to other platforms (10GB). For Git clients, we used GitHub Desktop, Sourcetree and Git Bash. Initially I recommended GitHub Desktop for the design and CG teams, but as we progressed with production we encountered a lot of problems. I wouldn’t recommend using GitHub Desktop on large projects as it lacks a lot of features which would allow one to back out of a spaghettified state.

We used a simplified Git flow model where we had master, develop and various feature branches. After reviewing and merging feature branches to develop, we’d merge develop into master and tag master with a release version which would then trigger an automated release build.

We decided that every discipline on our team must use Git, this is where we had a ton of problems and merge conflicts as very few people had prior experience with it. Nearing the end of production we managed to resolve most of the issues as everyone got more comfortable using Git. Informing everyone about frequent commits, short-lived branches and setting up proper .gitignore, and .gitattributes configurations seemed to have helped a bit as well.

The .gitattributes configuration that we used is pretty standard, apart from the Binary assets section which handles exceptional .asset files that contain binary data:

# Unity.

*.cs diff=csharp text

*.cginc text

*.shader text

*.mat merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.anim merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.unity merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.prefab merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.physicsMaterial2D merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.physicMaterial merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.asset merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.meta merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.controller merge=unityyamlmerge eol=lf

*.unitypackage filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# git-lfs.

# Image.

*.jpg filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.jpeg filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.png filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.gif filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.psd filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.ai filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# Audio.

*.mp3 filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.wav filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.ogg filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# Video.

*.mp4 filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.mov filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# 3D Object.

*.FBX filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.fbx filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.blend filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.obj filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# Wwise.

*.bnk filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# ETC.

*.a filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.exr filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.tga filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.pdf filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.zip filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.dll filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.aif filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.ttf filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.rns filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.reason filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

*.lxo filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

# Binary assets.

*Terrain.asset filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

LightingData.asset filter=lfs diff=lfs merge=lfs -text

The .gitignore is pretty standard as well, except for the Streaming assets section which focuses on silencing noise generated by Wwise:

# General.

/[Ll]ibrary/

/[Tt]emp/

/[Oo]bj/

/[Bb]uild/

/[Bb]uilds/

/[Ll]ogs/

/[Uu]ser[Ss]ettings/

# MemoryCaptures can get excessive in size. They also could contain extremely sensitive data.

/[Mm]emoryCaptures/

# Asset meta data should only be ignored when the corresponding asset is also ignored.

!/[Aa]ssets/**/*.meta

# Autogenerated Jetbrains Rider plugin.

/[Aa]ssets/Plugins/Editor/JetBrains*

# Rider

.idea/

# Visual Studio cache directory.

.vs/

# Gradle cache directory.

.gradle/

# Autogenerated VS/MD/Consulo solution and project files.

ExportedObj/

.consulo/

*.csproj

*.unityproj

*.sln

*.suo

*.tmp

*.user

*.userprefs

*.pidb

*.booproj

*.svd

*.pdb

*.mdb

*.opendb

*.VC.db

# Unity3D generated meta files.

*.pidb.meta

*.pdb.meta

*.mdb.meta

# Unity3D generated file on crash reports.

sysinfo.txt

# Builds.

*.apk

*.aab

*.unitypackage

Builds/

# Crashlytics generated file.

crashlytics-build.properties

# Packed Addressables.

/[Aa]ssets/[Aa]ddressable[Aa]ssets[Dd]ata/*/*.bin*

# Temporary auto-generated Android Assets.

/[Aa]ssets/[Ss]treamingAssets/aa.meta

/[Aa]ssets/[Ss]treamingAssets/aa/*

# Streaming assets.

/Assets/StreamingAssets/*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio*

/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks*

/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Windows*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Mac*

/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Windows/*

/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Mac/*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Windows/*.bnk*

!/Assets/StreamingAssets/Audio/GeneratedSoundBanks/Mac/*.bnk*

# Mac.

.DS_Store

# Files which are constatly edited by Unity.

/Packages/packages-lock.json

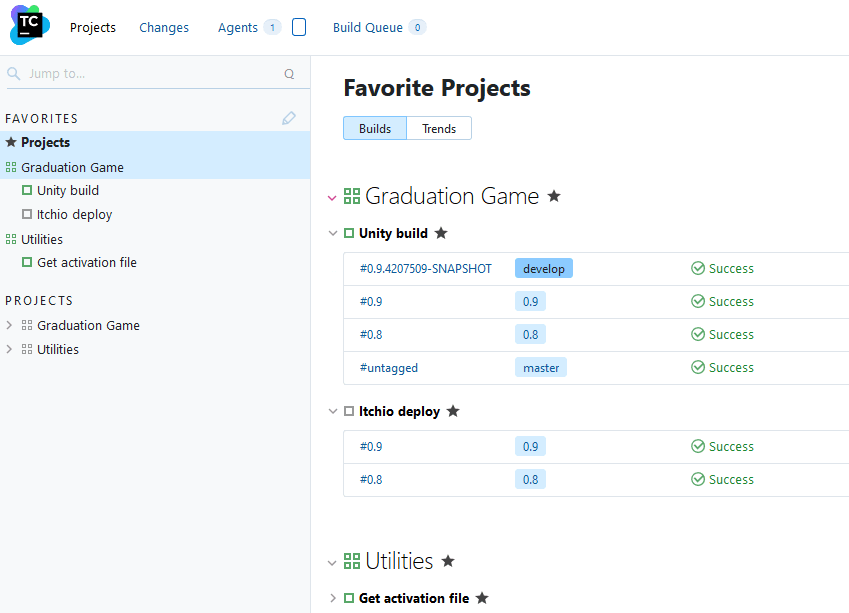

Automation #

Initially we spun up GitLab CI by following Automatically building and deploying Unity applications to itch.io. This setup was quite stable and quick to get up and running but as our projects grew it became way too slow as we had to wait 20+ minutes for a single build to complete. In addition to that, GitLab updated their CI limits to only allow for 400 minutes per group which we already exceeded by the time we got notified.

Afterwards we spun up a Linux machine on DigitalOcean with TeamCity. Setting this up was a lot more difficult as Unity didn’t like the fact that it was building on Linux inside Docker containers. We also had a bunch of issues bundling Wwise assets as well due to missing .dll errors. For future projects I would just use a Windows machine for automated builds.

One think that worked really well with automated builds were Discord messages. After each successful or failed build a message would be posted to specific Discord channels. This brought attention to failing builds from other disciplines and not only QA and programmer teams. In addition to that, waiting for our bots named Pinky and Brain to post a message on successful development and release builds was quite charming.

Workflow & features #

Working with a Unity project and maintaining a clean project is difficult on its own. Doing so in a team of 7 programmers is even harder. Even though a lot of features in the game are quite simple, having this many programmers made challenging as it is very hard to keep track of changes in Unity - a single change can break so many unexpected things. Nevertheless, I think we managed to develop a decent enough workflow, if there project were to be re-done also given a longer time-frame to develop the game, I think most of the problems would be avoided.

Prefabs #

Having so many people working on a Unity project we couldn’t directly edit the scenes as it created a ton of conflicts which were pretty much impossible to resolve. To avoid this, we tried to make it so that each feature could stand on its own as a prefab. We managed to achieve this to a certain degree on the programming team, however the level design and CG teams had some issues where a lot of objects were not converted into prefabs and could not be edited outside scenes. In addition to that, the project became rather messy as it was littered with randomly named prefabs all over the place. We did try to establish naming and folder conventions to avoid such mistakes, however given the short deadline chaos was unavoidable.

I was recently informed that this workflow can be achieved and improved without using prefabs as Unity provides

Multi-Scene editing feature. This actually looks like a better approach for when working with level specific objects, however I think for functionality related things, I’d still use prefabs. One issue with the Multi-Scene editing method is that one cannot make connections between objects in different scenes. However, I think this can be worked around by establishing connections between objects using ScriptableObject assets.

Trigger prefabs #

To avoid bottlenecks from the programmer team we decided to create a set of simple prefabs for the design teams instead of just coding every feature. We created a simple system where each component would expose a set of UnityEvent fields which would get triggered on specific actions, e.g. a player entered a trigger, a dynamic object hit something, etc.

Using this system we then made a set of nested prefabs and prefab variants where a number of these components would be chained together to achieve certain behaviours. For example if we wanted to play audio via Wwise when a player enters a zone, all we had to do was add a PlayerTrigger prefab with and slot in a WwiseEventAdapter into the PlayerTrigger components UnityEvent field. This approach removed the bottleneck completely - so much so that the level designers made too many levels that we had to cut some as there was not enough time to decorate them.

Example of a trigger component:

[RequireComponent(typeof(Collider))]

public class ColliderTrigger : MonoBehaviour

{

#region Editor Fields

[SerializeField]

[Tooltip("Should this trigger only if a specific collider enters it")]

private bool useWhitelist = default;

[SerializeField]

[ShowIf("useWhitelist")]

[Tooltip("Colliders which are allowed to interact with this trigger")]

private List<Collider> whitelist = default;

[SerializeField]

private UnityEvent onTriggerEnter = default;

[SerializeField]

private UnityEvent onTriggerExit = default;

#endregion

#region Unity Event Methods

private void Awake()

{

GetComponent<Collider>().isTrigger = true;

}

private void OnTriggerEnter(Collider other)

{

if (IsTrigger(other))

{

onTriggerEnter.Invoke();

}

}

private void OnTriggerExit(Collider other)

{

if (IsTrigger(other))

{

onTriggerExit.Invoke();

}

}

#endregion

#region Private Methods

private bool IsTrigger(Collider other)

{

return !useWhitelist || whitelist.Contains(other);

}

#endregion

}

This also allowed us to easily abstract interactions with Wwise. Instead of hard-coding communication with Wiwse via code, we created a bunch of adapter components which would plug into the UnityEvent based trigger system.

Example Wwise component:

public class WwiseEventAdapter : MonoBehaviour

{

#region Editor Fields

[SerializeField]

[Tooltip("Wwise event that will be triggered")]

private AK.Wwise.Event wwiseEvent = default;

#endregion

#region Public Methods

public void PostEvent()

{

PostEvent(gameObject);

}

public void PostEvent(GameObject obj)

{

wwiseEvent.Post(obj);

}

public void StopEvent()

{

StopEvent(gameObject);

}

public void StopEvent(GameObject obj)

{

wwiseEvent.Stop(obj);

}

#endregion

}

This setup worked really well as it turns out that most interactions in our game didn’t need anything too complex. I personally think it also greatly benefited the sound designers - initially they wanted to add some questionable code snippets from Wwise documentation into various places of the code, but this was avoided completely.

Game Events #

In some cases prefabs require communication with each other. This requires one to insert the prefabs into a scene and establish those connections via the editor. This is error prone as level designers were not always aware of all the connections that need to be made. To avoid this we implemented a system where prefabs would be able to communicate with each other using ScriptableObject assets by sending events over those assets. Due to that fact that in Unity .asset files live outside the scope of scenes we could create prefabs which would reference the said event .asset files and wouldn’t require any other connections. This essentially made it so that we could take a prefab, drop it into a scene and hit play without worrying that something is going to break.

This system worked well for certain scenarios where we had to trigger some global behaviour, e.g. player dies - show the game over screen. In addition to that, this system put a lot of power into the level designers hands - if they wanted to load the next scene or do something more complex, all they had to do was drop in a PlayerTrigger prefab and slot in a LoadNextScene event asset in the UnityEvent field. Same for the audio designers - a lot of functionality was achieved by simply adding listeners to events.

We ported most of the code that we used for this event system into a package

Unity Scriptable Objects. The system that we used and ported over is based on

Unite2017 repository. I highly recommend taking a look at it as it has some other useful suggestions on how ScriptableObject assets could be used.

Setup scene #

When using our custom event system it felt counterintuitive using singletons as it would go against the injectable nature of ScriptableObject assets. To avoid this we created a scene SetupScene which would be loaded before the current scene by using additive scene loading.

The SetupScene contains only manager objects responsible for the game state, UI, managers, etc. I think this was a really nice setup as it made it easier to reason about the global game state and allowed to completely avoid singletons. Our setup was not ideal as it had a flaw - the loading times while working from within the editor would be longer as in order to inject the scene we have to load the scene that the user wants to play, unload it, load the SetupScene and then additively load back in the unloaded scene. This is not a problem in a final build though. I have a feeling that this could be avoided by using Multi-Scene editing and manually adding in the SetupScene while working on the game.

The core Unity feature that enables the scene injection is the RuntimeInitializeOnLoadMethod attribute which allows execution of code before a scene is loaded:

public static class SetupSceneInjector

{

[RuntimeInitializeOnLoadMethod(RuntimeInitializeLoadType.BeforeSceneLoad)]

private static void InjectSetupScene()

{

var sceneIndex = Scenes.ActiveSceneBuildIndex;

if (sceneIndex.IsSetupScene())

{

return;

}

InjectSetupScene(sceneIndex);

}

private static void InjectSetupScene(int previousSceneIndex)

{

SceneManager

.LoadSceneAsync(Scenes.SetupSceneBuildIndex)

.completed += operation => OnSetupSceneInjected(previousSceneIndex);

}

private static void OnSetupSceneInjected(int previousSceneIndex)

{

Scenes.SetupSceneBuildIndex.SetActiveScene();

SceneManager

.LoadSceneAsync(previousSceneIndex, LoadSceneMode.Additive)

.completed += operation => previousSceneIndex.SetActiveScene();

}

}

In addition to that, the SetupScene must contain a GameObject with a component that loads the next scene if the active scene is the SetupScene. This is required for the final build as the SetupScene is the first one to load in the build order:

public class SceneHandler : MonoBehaviour

{

private void OnEnable()

{

SceneManager.sceneLoaded += OnSceneLoaded;

}

private void OnDisable()

{

SceneManager.sceneLoaded -= OnSceneLoaded;

}

private void OnSceneLoaded(UnityEngine.SceneManagement.Scene scene, LoadSceneMode mode)

{

scene.SetActiveScene();

sceneLoadedEvent.RaiseGameEvent();

// We're on the setup scene, load the next scene (menu scene). In the editor we don't

// want this to happen, as it might be useful to test the setup scene as it is.

#if !UNITY_EDITOR

var buildIndex = scene.buildIndex;

if (buildIndex.IsSetupScene())

{

StartCoroutine(LoadScene(menuSceneIndex, false));

}

#endif

}

}

Also, to get this to work a utility class is required as well:

public static class Scenes

{

public const int SetupSceneBuildIndex = 0;

public static int ActiveSceneBuildIndex => ActiveScene.buildIndex;

public static UnityEngine.SceneManagement.Scene ActiveScene =>

SceneManager.GetActiveScene();

public static bool IsSetupScene(this int buildIndex)

{

return buildIndex == SetupSceneBuildIndex;

}

public static void SetActiveScene(this int buildIndex)

{

var scene = SceneManager.GetSceneByBuildIndex(buildIndex);

SceneManager.SetActiveScene(scene);

}

public static void SetActiveScene(this UnityEngine.SceneManagement.Scene scene)

{

SceneManager.SetActiveScene(scene);

}

}

Note that this will cause lifecycle methods such as Awake and Start to fire twice when playing the game from the editor. This is due to the problem that I’ve mentioned previously.

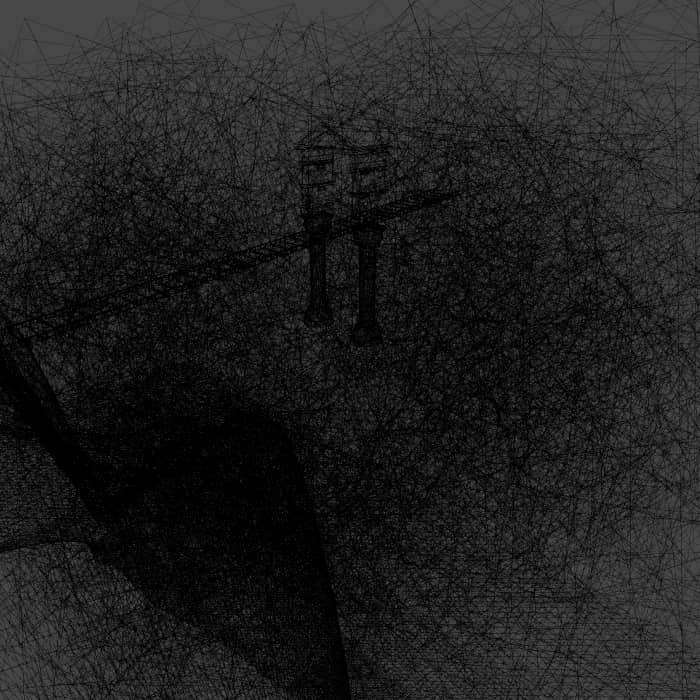

Core mechanic #

To implement the core mechanic we had to generate a mesh procedurally based on what the player draws on the screen. Getting mesh generation to work correctly was difficult. We couldn’t get it to work properly until the final moments of the production. In the end, we did a bit of searching and stumbled upon UnityPlumber which worked rather nicely, even though it still has flaws. Apart from that a lot of the challenges related to the core mechanic was integration with other features which I think are too specific to comment on.

I think the key takeaway is that we should have done more research in libraries which could aid in mesh generation. There are a lot of assets/libraries which could have been used to implement this.

Motion Matching #

One of the requirements from DADIU is that the game must use a Motion Matching system. Motion Matching is a way of playing animations using motion capture data instead of using state machines or blend trees. The benefit of using such a system is that one can achieve realistic animations and smooth transitions between poses at real-time. The downside is that it can sometimes feel unresponsive and hard to control. I’d recommend to watch Motion Matching and The Road to Next-Gen Animation to get more information on this topic.

At the time of writing this, Unity does not have a fully functioning system for this. There are some paid assets, but I have not tested them. Due to this, implementing Motion Matching was a huge challenge as none of us wanted to build a game which revolves around character animations. We couldn’t implement a working system during our first two mini games (this is the reason why we use it only in the first level and during the flashback). While working on our final game we still didn’t have a working system until we stumbled upon MotionMatching GitHub repository (thank you nashnie). We managed to implement the said repository into our game and use our own custom Rokoko animations in combination with animations from Mixamo. The end result was still buggy, but it sufficed.

Personally I think using such complex animation system doesn’t make much sense in a small game like this. It adds extreme amounts of complexity while offering little control over animations. However, for large or AAA games I think Motion Matching could be an invaluable tool.

Performance #

For rendering we used Universal Render Pipeline. This was decided as the art direction for the game did not require that many fancy features. I think this was the right decision as we didn’t have that many performance issues related to rendering. We did encounter some problems with our custom shader during the last week of production, however most of them were minor issues. The biggest challenge related to performance was the VFX Graph. We went a bit overboard with some particle systems which tanked performance pretty badly. We didn’t want to reduce the particles too much as some scenes relied on having huge emission rates, e.g. clouds. If we had more time however, I think this could be resolved by adding a simple graphics options menu or using a different system entirely for rendering huge volumes of clouds.

Another challenge we faced was related to colliders. Most static objects in our scenes are made out of modular prefabs. For example, if I wanted to create a skyscraper, I’d stack up a bunch of house prefab modules and call it a day. The issue with this approach was that each module had its own detailed MeshCollider component. This tanked the performance pretty badly, so much so that some scenes would take 30+ seconds to load on some development machines. The solution for this was to manually go through each prefab and replace MeshCollider components with a set of primitive collider components and make sure they are marked as Static. Having done that we then encountered a problem where the player would get stuck in between the gaps of the primitive colliders - we didn’t have enough time to solve this one. I have a feeling this is due to the fact that our colliders, and the player mesh are too thin.

Command console #

To help out with testing development and release builds for QA we implemented a developer console (try it out by pressing F12 while in-game). However, it wasn’t as useful as expected as QAs would have the editor open most of the time when testing. Yet, we encountered some tricky situations during presentations where the game would bug out, or we’d have to quickly showcase a specific area - this is where the command console shined the most.

I believe if such a tool were to be used to its fullest potential it has to be implemented as early as possible. I think having commands which would allow pointing out bugs would be invaluable, specially for bigger projects. For example, a command to create a string that could be pasted into a ticket management system to describe a bug, then the same string could be re-used to get to and trigger that bug later on.

Custom Unity editor tools #

Due to the sheer amount of assets we had to automate some steps, such as prefab creation. It is quite easy to build custom tooling for the Unity editor, and the payoff is immense. The tool that I wish we would have implemented was automated composite convex hull creation, that would have saved a lot of time and possibly would have resolved the issues we had with collider performance and player getting stuck in collider gaps. Creating colliders by using Unity’s primitives is tedious and time-consuming. For future projects I will try to explore the extensibility provided by Unity’s editor even more. In addition to the automated convex hull creation I’d like to create some utilities which would allow settling of dynamic objects.

Closing notes #

All in all the DADIU programme was extremely fun and challenging. Honestly, I chose this programme as a safe way to see if game development is something I would like to do, and it did not disappoint. Having met so many awesome and creative students, and professionals is an experience I’ll never forget. I’ll take note of all the technical challenges that we faced for future projects and will write more posts when I learn something new. Thank you for reading and have a nice year 2021!